Teaching History 200: Out now

The HA's journal for secondary history teachers

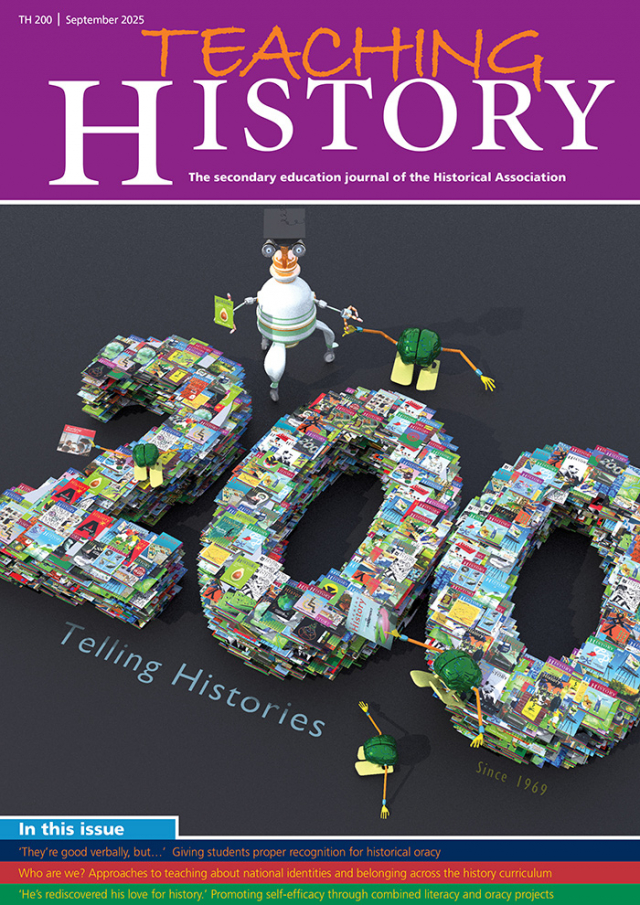

Editorial: Telling Histories

Read Teaching History 200: Telling Histories

In his recent book on the experiences of Parisians in the years leading up to the French Revolution, Robert Darnton describes the Tree of Cracow, a large chestnut tree in the garden of the Palais-Royal in central Paris.1 ‘Nouvellistes de bouche’ (oral newsmongers) gathered under it to exchange the latest news, and ordinary people stopped by ‘to satisfy their curiosity’.2 Some of the listeners scribbled notes, which they would share in nearby cafes. Such notes were later confiscated by police when they searched prisoners in the Bastille, and they can still be seen in the Bastille archives, revealing ordinary people’s responses to the tempestuous events. When Darnton tells the myriad stories as a history of these problematic years, he places sources at the centre of his narrative.

Darnton’s book and the Tree of Cracow resonate with many ideas in this edition. First, the enduring power of the spoken word. Second, the ‘flourishing of storytelling’ as part of historical scholarship and therefore history teaching.3 Third, the relationship of stories to histories and to source material, discovering and questioning whose stories are being privileged. We need to ask not only the purpose of the stories we tell, but also how those stories are experienced by our students. Such themes of disciplinary history have been a constant of this journal since its inception in 1969. Throughout the 200 editions, there has been a consistent focus on history teachers sharing innovative practice, whether in response to the needs of students or in reaction to shifts in historical scholarship or government policy.

Three articles in the edition take up the idea of oracy, with the authors sharing a desire for subject-specific, historical talk. Toby Dove found his Year 13 students rather reluctant to answer questions in class. He and his department decided that the solution was to be more deliberate in embedding high-quality student talk throughout the taught history curriculum. This aspiration raised questions about planning, assessment and progression in disciplinary oracy, which Toby shares with vivid examples.

Jonty Haywood was keen to develop a culture of extended reading among his younger students, but he also wanted them to have a more confident voice when engaging with history. He gave a term’s worth of homework: to read a non-fiction history book and then a five-minute ‘creative presentation’ task for students to summarise what they had learnt. Haywood describes a lively engagement with the past from his students, as they shared a variety of histories. Marshall and Proctor, working with student teachers, found that they often heard only the voices of confident students in lesson observations. They promoted the use of mini whiteboards as a specific device to encourage historical dialogue between students and between student and teacher. Their practical wisdom is worth sharing with novice teachers or others who may not have experimented with the power of mini whiteboards to promote every student’s chance to talk.

Artificial intelligence raises its own questions around histories and stories. John Simkin shares his memories of technology in the history classroom, from early simulations to the establishment of Spartacus Educational. Through a long lens, he raises suggestions for the role of artificial intelligence in history education, making a case for the importance of the history teacher. Whether from the internet or other sources, students experience different grand narratives, which can have a profound effect on their beliefs and identities. Daniel Magnoff and colleagues asked their Year 7 students how they thought nations were created. Suspecting influences of a singular ‘island story’, they then explored how far it was possible to help their students move to a more nuanced conception, challenging them with the idea that identities are invented. Sequences of lessons to support this shift are described, from the intentionally provocative ‘The invention of England’ in Year 7 to LGBTQ+ history in Year 9.

Responding to the recent ‘flourishing’ of stories in history classrooms and history textbooks, Holliss and Carroll were keen to investigate the potential use of stories with Year 12. They were explicit that the stories told out loud to the class would be highly stylised, presenting initial content in an engaging and dramatic manner. They report that writing such stories was far from easy, with the need to balance disciplinary rigour, engaging storytelling and diverse representation. This thought-provoking article offers challenge on how to teach the French Revolution at A-level, but the messages are relevant for storytellers at all levels. The authors raise the point that students need to be able to move beyond recounting stories and to appreciate how historical narratives are constructed and challenged. Far from a simple, happy ending, Holliss and Carroll demand sequels to their work, so please read, replicate and reply.

Beyond these articles, there is so much more in this edition. Don’t miss Elizabeth Carr’s Cunning Plan on teaching the Black Death, with a focus on climate change. Or Kerry Apps’s Polychronicon on global histories. And then there is the final page, which explores 200 editions of Teaching History in a little more detail. We very much hope you enjoy the edition, but keep your scribbled notes safe, as you never know where they might end up.

References

1 Darnton, R. (2023), The Revolutionary Temper: Paris, 1748–1789, London: Penguin.

2 Ibid., p. xx.

3 Holliss C. and Carroll J.E. (2025), ‘Story time? Investigating using stories about the French Revolution with Year 12’ in Teaching History, 200, Telling Histories Edition, p.18.