Polychronicon 162: Reinterpreting the May 1968 events in France

Teaching History feature

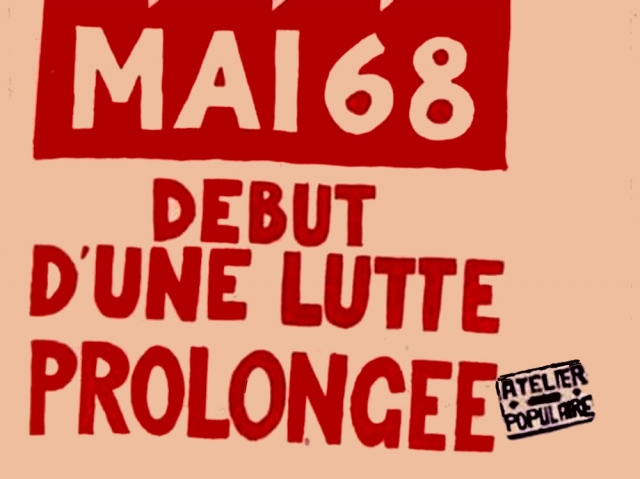

As Kristin Ross has persuasively argued, by the 1980s interpretations of the French events of May 1968 had shrunk to a narrow set of received ideas around student protest, labelled by Chris Reynolds a ‘doxa’. Media discourse is dominated by a narrow range of former participants labelled ‘memory barons’ – motivated by a wish either to uphold the ideals of the 1960s, or engage in moralistic denunciation of them. Yet there is now a tendency towards serious empirical research, transcending simplistic debates about whether or not 1968 was a good thing.

The clichéd received wisdom is the generational saga of a certain in-crowd in Paris’s Latin Quarter, portrayed as hippies kicking back against their parents for free love and revolution. Supposedly there was no serious violence: it was all good fun – a quintessentially French affair, unlike the terrorism that followed in Germany and Italy. The revolt is depicted as a fundamentally unserious one, by revolutionary poseurs with no grasp of reality. Students tried to get Renault workers to join them, but the Communist-voting workers, who just wanted a pay rise, told these privileged students to go away. The party lasted a few weeks, a lot of Situationist slogans...

This resource is FREE for Secondary HA Members.

Non HA Members can get instant access for £2.49