Teaching History 197: Out now

The HA's journal for secondary history teachers

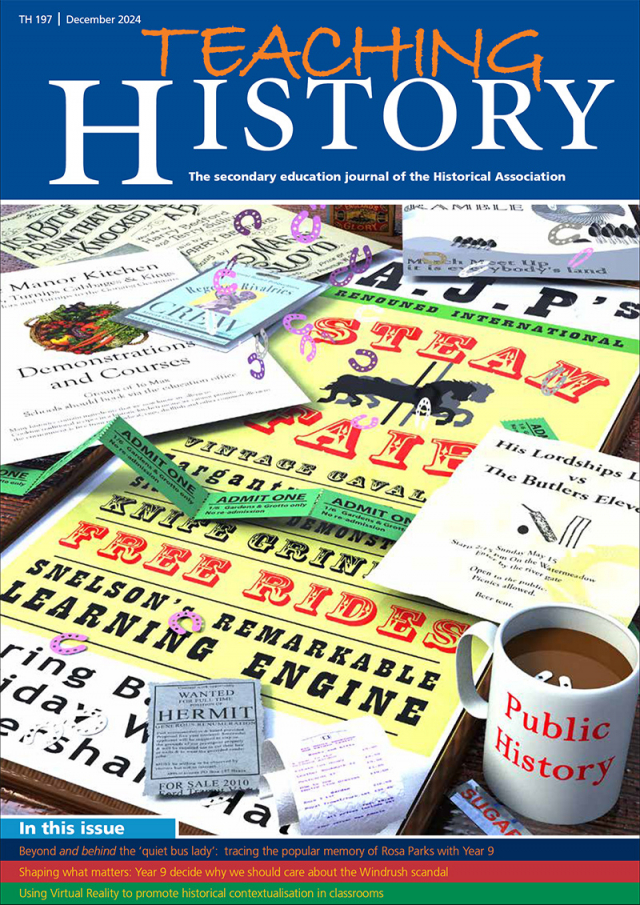

Editorial: Public History

Read Teaching History 197: Public History

Public history is history facing outwards: engaging with the public sphere beyond the ivory tower of research and scholarship in universities. In a recent essay entitled ‘Glorious memory’, Hicks writes of ‘an explosion of new public histories’ in recent decades, ‘led by communities from the grass roots’ and experienced through screens, or encountered in museums, historical sites and the landscape.1 Historical knowledge is produced, mediated and consumed in public spaces.

School history is history in a formal education setting, and yet it has a public-facing dimension. The content of the history curriculum is debated in the media. When we plan the history curriculum for our pupils, we know that this carries responsibility because the history we teach in the classroom will shape the way our pupils see the world. ‘We use history to understand ourselves,’ writes Macmillan, ‘and we ought to use it to understand others.’2

Each of the authors writing in this edition explores the teaching of history at the interface between education and the public sphere. Several make the case for history teachers to consider not only what their pupils will understand about history as a discipline, but also how they will use that knowledge to understand themselves, others and the world around them.

Ed Durbin introduces his pupils to public history through an enquiry exploring the popular memory of Rosa Parks. Rather than merely debunking the ‘inspirational fable’ of Parks’s life with the meticulous scholarship of her biographer Jeanne Theoharis, Durbin shows his pupils how the popular memory of Parks developed over time. His article exemplifies how pupils can study popular interpretations – public-facing history – as rigorously as scholarly ones. Durbin conveys the value of exposing such interpretations to critical scrutiny in the classroom.

Tom Pattison, writing the ‘Triumphs Show’, similarly took inspiration both from historical scholarship and from popular interpretations: in this case, from the preconceptions and misconceptions his pupils brought to their history lessons.

He and his team challenged these through curriculum redesign, influenced by Peter Frankopan’s The Silk Roads. Under the overarching question ‘How did the Silk Roads shape the world?’, they introduced a more global history of the medieval period and provided a means to change pupils’ perceptions of the world around them.

Mark Fowle’s starting point was the public commemoration of the first Stephen Lawrence Day, on 22 June 2018. This prompted him and his colleagues to consider the kinds of historical understanding of recent history their pupils would need to be able to contextualise the present, particularly the Windrush Scandal and ‘hostile environment’ policies relating to immigration. In the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder, Fowle faced the challenge of teaching pupils to navigate the relationship between present and past. He turned to historical significance as a lens through which his pupils could examine this relationship, anchoring their analysis in knowledge of the historical context.

Like Durbin, Foster is interested in popular, or social, memory – the ways in which different people have used the past and made history. Some pupils may encounter stately homes through ‘days out’, as the site of cafes and adventure playgrounds, although many more will not have these experiences. Foster shows how an enquiry into changing attitudes towards stately homes, and their journey towards a status as treasures of ‘national heritage’, can educate pupils in the public understanding of the past.

Joris Van Doorsselaere, working in Belgium, found himself, like Fowle, working within and responding to a particular political context – the politicisation of school history in the public sphere. He sensed a tension between calls for disciplinary history and pressure from the political right for a national ‘canon’ of Belgian history and heritage. To mediate this tension for his pupils, Van Doorsselaere set out to teach them how to deploy an historian’s disciplinary arsenal to study the history of a local building, and in so doing to engage in public history and to explore the relationship between heritage and identity.

As a museum educator, Clare Lawlor is a public history professional. She discusses the design of the new Holocaust learning programme at the Imperial War Museum, and the evidence for its impact on students’ historical thinking. Using digital technology and dialogic teaching, Lawlor and her colleagues show how to realise the potential of sites of public history, such as a museum gallery, to prompt critical reflection about the relationship between the past and the present.

Rather than take students to a gallery or site, Pieter Mannak and his co-authors brought virtual reality experiences to pupils in the classroom. Mannak and his colleagues investigated how an experience designed to bring history to life for public audiences can contextualise historical source material in the classroom Their warning of the need for pupils to be taught to recognise VR as a representation or interpretation of the past, however, resonates with Durbin’s and Foster’s calls to educate pupils about the construction of public history and popular memory.

References

1 Hicks, D. (2021) ‘Glorious memory’ in H. Carr and S. Lipscomb What is History, Now? How the past and present speak to each other, p. 106.

2 Macmillan, M. (2009) The Uses and Abuses of History, London: Profile Books, pp. xi-xii.