Teaching History 190: Out now

The HA's journal for secondary history teachers

Editorial: Ascribing significance

As the collection of articles for this issue of Teaching History began to take shape, its title remained rather uncertain. While some of the articles referred explicitly to teaching historical significance, others focused more on teaching students the processes involved in shaping stories about the past. Should the focus be identified as primarily concerned with ‘significance’ or would ‘interpretations’ be more effective as a summary of the issues addressed?

In fact, the two concepts are inextricably intertwined. The processes involved in the construction of any interpretation– all the decisions made about which stories to tell, about what and whom, and from whose perspective – are judgements about historical significance. The decisions made tell us what matters to the historians and –and to the artists (novelists, filmmakers, etc.) – who construct those stories. In this sense, historical significance is not a second-order concept in its own right; it is a ‘meta-concept’ sitting above almost every choice made in the pursuit of history. There is, therefore ‘no reason to worry about whether “this is an interpretations enquiry” or “this is a significance enquiry”. It can easily be both.’ 1

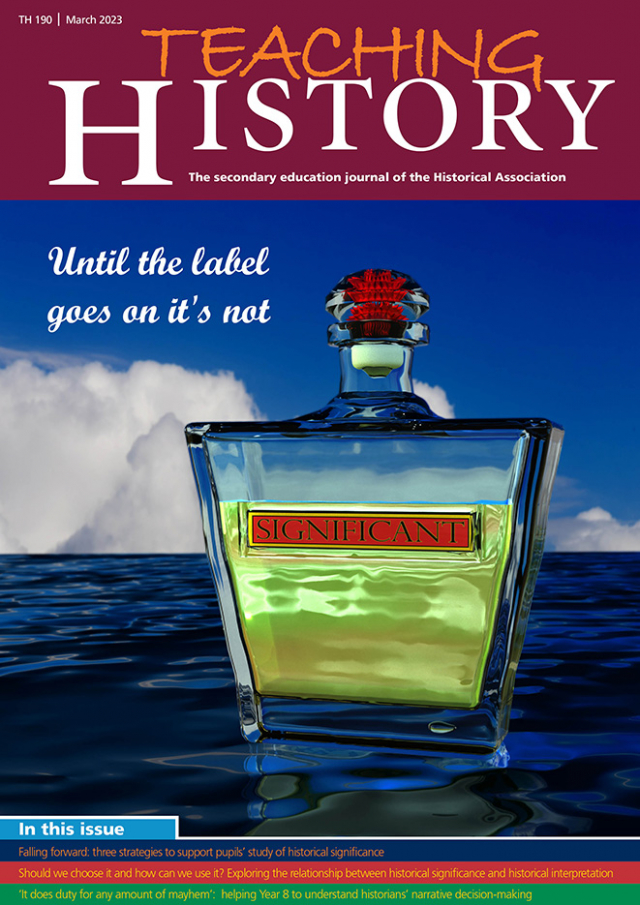

The working title thus became ‘Significance and Interpretations’ – until our cover designer intervened! He was struck by the critical principle that historical significance is never a fixed, permanent property of an historical event. It is a reflection of the judgement made by others (the subsequent storytellers), who ascribe significance through their own decisions. His ambition to represent that key idea ultimately moved significance to the fore. The visual metaphor that he chose – the power of the labelling process itself in determining significance – is simple but effective. It might perhaps help in overcoming a common source of confusion for history teachers.

Paula Worth offers similar help in tackling common problems. Readers will value her honesty in sharing her own early difficulties in teaching about historical significance, before going on to describe the imaginative metaphors that she developed, along with other productive ways forward. But her suggestions come with a warning not to repeat her attempted short-cuts – seizing on good ideas without fully understanding the specific teaching purposes for which they were created. Jane Card also offers several practical suggestions, rooted in painstaking research into visual interpretations of past events (specifically the Norman Conquest and Spanish Armada). She demonstrates how images can convey compelling messages about the significance of particular events; memorable ‘little stories’ often shape interpretations of the larger story of which they form a part. The article suggests several ways in which teachers might alert students to the enduring power of popular interpretations encoded in visual formats.

The power of the visual to convey enduring messages and judgements of significance is also fundamental both to Gemma Hargraves’s Cunning Plan and to the article by Jen Turner and Arthur Chapman, examining the decisions made in the process of historical narration. Inspired by two graphic novels about the Peterloo Massacre, Turner and Chapman devised a Year 8 enquiry, examining three kinds of decision related to storytelling: questions of perspective, of focus, and of scene and summary. In each case, students were encouraged to consider both the positive decisions about what should be included and from whose perspective and the negative implications in terms of what was left out.

Andrew Slater wanted to show students that judgements of significance are also central to teachers’ decisions about what to include within – and exclude from – the school history curriculum. By presenting the curriculum as a product of deliberate decision-making, Slater encouraged Year 7 to begin thinking critically about the criteria on which such decisions are based. By deliberately selecting an unfamiliar past society – the Khmer Empire – and a limited number of criteria, he enabled his students to explore how judgements might be made, first about that particular topic and then about other topics, as alternative contenders for inclusion in the curriculum.

Rachel Foster explains her choice of the story of Saint Foy, as a means of illuminating for Year 7 all the most significant developments of the early medieval church. Her account offers rich insight into the wide-ranging criteria that actually inform a history department’s curricular decisions. Foster too admits past weaknesses in her planning – a tendency to shy away from telling the big outline stories that are needed to balance depth with overview. Her solution came from new approaches to biographical history: telling the story, not of an individual, but of a family or an object over time. Foster’s choice of Foy’s reliquary statue demonstrates how much can be revealed by a single, well-chosen story.

While Slater encouraged Year 7 to recognise that their teachers’ decisions could be subject to critique, Peter Turner prompted his A-level class to question the particular interpretation that he was presenting to them. In deliberately staging an argument with a colleague (about the reasons for the Reds’ victory in the Russian Civil War) his intention was not merely to illustrate how different interpretations can be legitimately constructed but to make students aware of the shared community of enquiry within which all historians operate.

References

1. Historical Association (2020) ‘What’s the wisdom on…historical significance?’, in Teaching History 181, Handling Sources Edition, p. 54.