Teaching History 178: Out now

The HA's journal for secondary history teachers

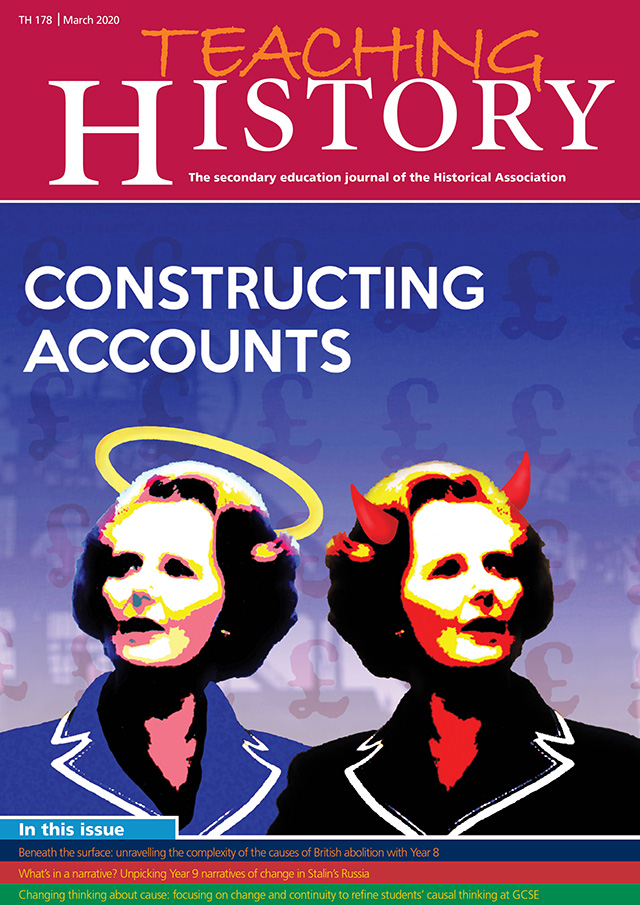

Constructing Accounts

Teachers of history have long recognised the tensions inherent in our role. We must deal with the existence of notions of a core narrative (or narratives) of areas of the past, communicating what those notions are while enabling our students to engage critically with the narratives themselves and the interpretative frameworks behind them. We must enable our students to interact with the past as historians while recognising that they are not fully historians yet. We must enable our students to identify their own historical consciousness, while interacting with others’ historical consciousness. We must help our students to build a (contentious) narrative around which they can form an analysis, which is most likely to be what they are assessed on. All in, if we’re lucky, a couple of hours a week.

This edition of Teaching History presents a series of approaches to the way in which history teachers might enable their students to construct their own accounts of the past, navigating the accounts constructed by others. Alex Ford has written about the overlap between the second-order concepts of causation and continuity and change. His central thesis is twofold. First, given that students can effectively get away with poorly substantiated causal reasoning in a short examined essay, we should make sure that we serve them well as future historians, not just as future examination candidates, by giving them the frameworks to produce richer and more nuanced work. Second, and as a consequence of his first observation: this is really, really difficult. His solution is to focus on the changes in direction of a narrative. At the changes (and counterfactually at the continuities) can be found the causes. Ford found that when students were helped to think about this, and trainee teachers were helped to think about how to work on this with the students, their thinking was necessarily so complex that they more naturally produced complex and substantiated argument, and were forced to construct their own narrative accounts of the past.

Ford also presents a model of professional reflection. He spotted a problem, and then looked around lots of classrooms and did a lot of reading – pedagogy, history and the philosophy of history – to come to a hypothesis about what he might do about the problem. Michael Taylor’s approach is very similar, and equally rooted in these different types of scholarship. He presents the way in which he and his department have combined three factors to ensure that the essays their students write are rigorous and well reasoned. In a setting in which approaches to teaching and learning are deliberately limited to ensure consistency, Taylor’s department uses a method known as Direct Instruction to secure deep, rich knowledge. Then they break down the question, which drives the students’ learning, into a series of nuts and bolts, and ensure they are assessing both the substantive historical knowledge and the procedural or organisational concepts being taught. Finally, in the case of essays, they… do not necessarily ask their students to write an essay. For Taylor, an essay is like running a marathon – a goal for which the training cannot consist simply of running marathons.

Elizabeth Marsay, too, has contributed an article recognising that the link between causation and narrative must be strengthened to allow students to construct rich and substantiated accounts. She also draws on scholarship to consider exactly what causation means in the classroom. Her focus is on the teaching to Year 8 of the abolition of the slave trade, and she uses competing narratives quite deliberately to muddy the waters for her students. The key is not so much how she therefore complicates matters, but the way in which she enables her students to emerge from their analysis of multiple historical sources and interpretations, emboldening them to take risks in their thinking and arrive at more nuanced, and well-expressed, judgements. James Ellis has also focused on a single enquiry: in his case, narratives of change in Stalin’s USSR with Year 9. He fits his ideas explicitly into the framework of what had concerned him about his Year 11 students’ attempts at forming a narrative about the American West. Ellis’s approach was to challenge his students not to produce an analysis based on a narrative, but to produce the narrative itself. With Figes’s scholarship underpinning their efforts, Ellis’s Year 9s were asked to produce a narrative which contained both individual stories and a general account of what happened in the USSR under Stalin. Ellis ends with a reflective description of what had worked well, and it is as much an analysis of what to do with Year 9 as it is of the problematic process of creating accounts in history at all.

Maria Vlachaki and Georgia Kouseri also set out to help their students to integrate different types of narrative into as coherent a whole as they could. They decided to use their students’ rich and diverse family histories to do this, in response to recent changes in the Greek curriculum which they both deliver. Their schools are very different. One has younger children with a high proportion of first generation immigrants; the other has older children many of whom are second-generation immigrants. They asked their students to create their own family narratives, and were then able to combine their own and their students’ efforts to think about the relationship between family narratives and a general narrative of Greek history, and how students of different ages respond to such concepts. These constructed accounts show up the truism that while history is rooted in the past, its telling is often about the present. We also have our regular features including a redesigned Polychronicon asking What’s the argument about…? We hope that you enjoy our own attempts to collate and construct an account of what constructing accounts might mean.