Teaching History 196: Out now

Editorial: Demanding History

Read Teaching History 196: Demanding history

History can be a very demanding subject, in a number of senses. The past can make demands on us – it can demand attention and demand to be addressed. There can, as it were, be historical as well as financial ‘final demands’, reminders of historical debts needing to be repaid, of past injustices that remain unacknowledged and unreparated.

Our students can make demands of us also – looking to history and to history teachers for answers and explanations of urgent and troubling aspects of the present, often expecting that we account for silences and absences in curricula and lessons; demanding that we make histories speak to them and their present interests and concerns. The accounts of the past that we offer can themselves, then, be called to account.

Learning history makes cognitive demands too, of course – on pupils’ memories, on their abilities to conceptualise and reconceptualise the often very different worlds of the past, and on their abilities to read and to write. History can also be very hard to navigate and can raise sensitive and controversial questions, making demands on history teachers’ abilities to navigate these respectfully and inclusively in ways that enable dialogue and learning.

We can also, of course, make demands on history as educators, requiring it to be – and wrestling with resources, curricula and other impediments to make it be – more rigorous, engaging, demanding, and so on.

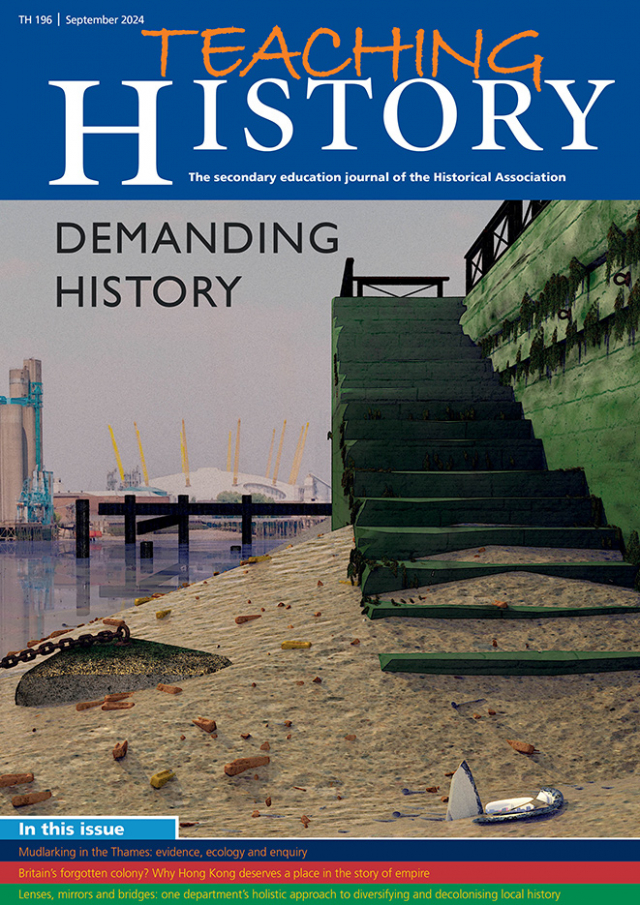

Maryam Dorudi’s article addresses a number of these issues. She wanted history to engage, challenge and interest her students. Focusing on the Thames’s riverbanks as a concrete source of history visible in her school locality, was a strategy that might help students explore London’s historical identities and their own, and that might also allow them to explore what it means to be an historian. Evidential and environmental questions arose – and ethical ones, not least about the ethics of exploring the past without damaging it or the ecosystems and sites it can be discovered in.

Ollie Barnes encountered Hong Kong history on honeymoon and, powerfully, in the classroom in Nottinghamshire. Historical changes in the former colony’s present had resulted in increasing numbers of Hong Kongers arriving in school. This history demanded attention – important historical changes were in process and pupils needed to understand them. It was important, also, that students came to appreciate the intimate historical links between Hong Kong and Britain, and this history was largely hidden, or at least almost entirely absent, in the history curriculum. Barnes outlines how his department integrated an enquiry about Hong Kong’s history into their curriculum and reflects on the impact that doing this had on students’ perceptions.

Reflecting on how well her pupils’ analyses of similarity and difference responded to the demands that these concepts made on them, Molly-Ann Navey set out to design new sequences of lessons that would help pupils to develop their argumentation. Navey’s article details part of her department’s journey, beginning with a Year 8 enquiry on the Home Front in the First World War. Realising that the interplay of conceptually focused vocabulary and knowledge growth was not quite working, she tried again, this time with Year 9 and an enquiry on post-war Britain. Learning from the pitfalls of the first enquiry, Navey and her department were able to foster more independent, authentic and integrated writing in response to questions about similarity and difference.

As was the case for many heads of history, Jack Brown was prompted by the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020 to reflect afresh on the content and questions asked within his school’s history curriculum, paying particular attention to local history and to the opportunities that focusing on the local area presented to engage pupils’ interest, and also to bring pupils’ diverse histories into contact with history in class. In this article he sets out the principles and purposes that framed his department’s approach to developing and refining a series of local history enquiries across the course of Key Stage 3. He explains and illustrates the decisions taken by the department, which extended to their choice of GCSE units and their determination/resolve to engage critically with the legacies of colonialism.

Alex Blelloch observed that many of her students struggled to engage fully with the demands that historians’ writings made. She also became concerned that her department’s curriculum provided limited opportunities for younger students to engage with historians’ works. Blelloch’s article sets out her reasons for wanting to open up the demands of historical texts for her younger students and the opportunities she created and the methods that she developed to encourage them to look at texts more deeply. Using examples from her teaching of students aged 11–14, she outlines how she used a simple visual metaphor to help students read and re-read selected texts. Blelloch then describes her methods for using this metaphor to improve students’ access to historians’ texts. The result was richer understanding of historians’ arguments.

Perhaps opportunities will soon arise for the history community to revisit debates nationally about how demanding history should be in seeking sufficient place and time in the school curriculum? So much to do, so little time.