Teaching History 167: Out now

Journal

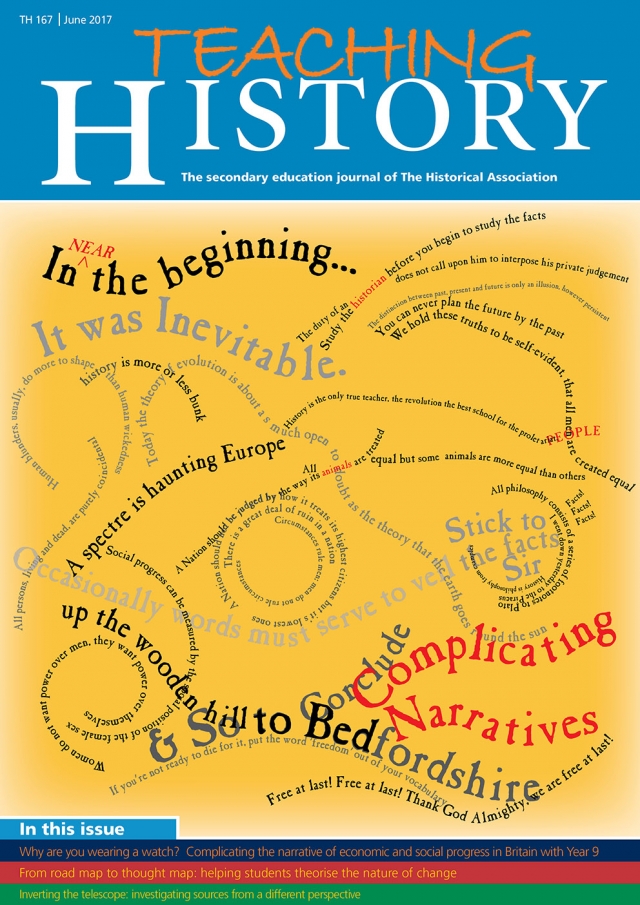

Complicating narratives

Narratives speak far beyond the facts they contain. The very act of choosing two facts to put together in a sequence, and the way they are put together - whether implying causality, linkage or independence – sends messages to the reader which can be radically different from those in another account with the same, identical facts. Every narrator wields this hidden power so any assumption that there is a neutral, non-controversial, ‘correct’ narrative is disingenuous in the extreme. Facts can certainly be accurate. A chronology of facts can also be accurate chronologically. But a narrative is artistry. It is an artistry shaped by choosing, arranging and linking, and the artist will persuade and influence, tease and delay, always with an audience in mind.

Yet at least with written narratives we can train ourselves and our students to spot this artistry. We can learn to question the choice of fact or wonder at the effect words are having on the way a writer attributes importance. But what of those narratives which we barely recognise as narratives? What of those well-known stories such as Nixon and Watergate, the 1960s, the industrial revolution, the Tudors? These stories we hold in our heads almost like images. They are mental schemes of how things were and how one thing led to another, all held together as a package or an overall impression. It is too easy to forget the assumed narratives that have shaped that impression.

The history teacher’s eternal challenge is, on the one hand, to harness this glorious story-telling power, to use it to embed the winning narrative and to give pupils the memorable connections that can only gain meaning as story and only be remembered as story. Without story, nothing makes sense and nothing can be assimilated. On the other hand, we must equip students to take the narrative apart, to see the hidden narrative and the hidden – even unconscious – argument in any narrative, and then to consider how different emphases, new evidence, different questions or new angles can alter that narrative profoundly. We are in an eternal conundrum – we need story but story must always be challenged. We must simplify using story, but we must complicate using story too.

This edition sees several teachers complicating well-worn narratives for their students and enabling students to have the confidence to engage in complication themselves.

Hannah Sibona set out to complicate her Year 9 students’ understanding of the industrial revolution. In order to raise questions about standard textbook narratives concerning change, she made use of the classic work on the English working classes by historian E.P.Thompson. With a focus on how people during the industrial revolution experienced time – its commodification and its recording – Sibona built a sequence of activities designed to help students see the way in which economic and sociocultural change were inextricably linked and what is lost when they are described separately. Sibona also complicated for students’ the pattern and process of change, making comparison with wider developments in the use and experience of time, including those in the present. Elizabeth Carr also sought to complicate narratives of the industrial revolution, but in a very different way. Drawing on a recent work, Liberty’s Dawn, by Emma Griffin, Carr challenged her pupils to work out what claims can defensibly be made about the experience of working people, and to consider how certain source material belies the conventional generalisations.

Rachel Coleman, concerned at her pupils’ love of definitive answers, tackled the need for complication head-on. Coleman decided to help her high-attaining Year 9 class to welcome and enjoy history’s complicated character. She therefore required them to complicate various common impressions of the 1960s, then to examine further source material and contrasting interpretations by historians. Coleman’s hexagons provided an ingenious way of allowing students to consider not only the various components of accounts of the 1960s but how they might be selected and reconfigured differently. Her students finally had to re-think their original assumptions, producing new and complicated narratives of the 1960s. It was Year 7 students’ fixation with Henry VIII’s wives that gave Warren Valentine similar starting concerns. Valentine tackled the problem with a ‘thought-map’ task. His students had to re-work their knowledge of the Tudor monarchs so as to complicate their earlier narratives of the Tudors, reconfiguring and rerelating the material so that it told new stories. Rosalind Stirzaker, teaching in Dubai, started in a different place – with the raw materials from which stories are constructed. Stirzaker asked students to take control of the evidence from which they would like future historians to tell their story. The range of discussions that resulted were fascinating. Students found themselves considering who or what causes source material to survive and how profoundly its creators’ purposes differ from those of the historians who will use it as evidence.

In a slightly different vein, Jim Carroll focuses on the role of oral rehearsal in ensuring that students grasp the multivoiced character of disciplinary history. Carroll’s work shows how students of history must live with others’ efforts to complicate what they thought they knew: for the historian’s way of being is dialogic. Carroll shows that by entering into the play of voices orally, students start to realise that in their written arguments, too, they must convince, counter or concede, rather than argue into a void. An account – whether its argument is explicit or implicit – can never stand still. It is always generated in response to another’s case and then it must stand ready to re-shape itself, yet again, in response to another’s question, another’s way of telling, another’s analysis.