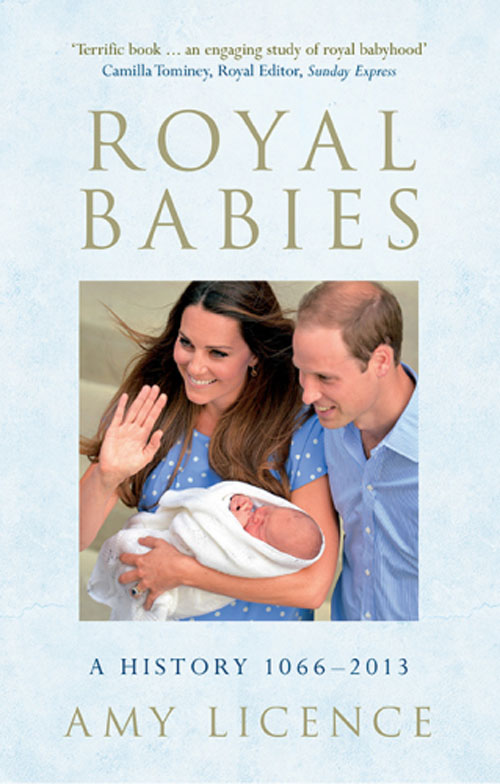

Royal Babies. A History 1066-2013

Review

Royal Babies. A History 1066-2013, Amy Licence, Amberley, 2013, hardback, £16.99, 208 pp., ISBN 9781445617626

Retrospectives of the year 2013 have viewed the birth of HRH Prince George of Cambridge not only as signifying renewal of the monarchy with the prospect of continuity of the descendants of the house of Windsor into the twenty-second century but also as the potential renewal of a nation tentatively emerging from recession. Inevitably, every snippet of information about the new royal arrival is gleefully transmitted by a media, which hasn't always treated the house of Windsor respectfully. The book under review provides a perspective of over a millennium in which to explore the significance of this latest royal birth from a writer who describes herself as a medieval and Tudor historian. Indeed we are perhaps told rather more than we need to know about the author's credentials for writing this book, including that ‘she took four long years to conceive' her second child, that both her own babies were born naturally and that she is also author of In Bed With the Tudors: The Sex Lives of a Dynasty from Elizabeth of York to Elizabeth I, which a Daily Express reviewer is quoted as proclaiming ‘explores what really went on in Henry VIII's bedroom'.

The author asserts that ‘royal babies have excited interest since before their births for more than a millennium'. Inevitably the more unusual features of royal births and the lives, which they inaugurated, are highlighted, some of them now virtually forgotten. Three examples, in particular, illustrate this point. The first, Edward, the eagerly anticipated son of Edward IV (after three daughters in an era were male primogeniture held sway) and ‘his beautiful but unpopular wife ‘Elizabeth Wydeville, reigned only briefly as Edward V at the age of twelve before his demise as one of the ill-fated princes in the tower. The second, the future Henry IX, son of Catherine of Aragon, whose brief seven-week existence, had he survived longer might, the author speculates, have prevented his father from having six wives, and thereby deprived British History of one of its biggest box office draws in terms of regal marital insecurity. The third, another Prince George, the stillborn son of Charlotte, Princess of Wales, who perished with his mother as a result of his birth in 1817, whose survival may perhaps have delayed Victoria's accession to the throne twenty years later and curtailed her monarchical longevity.

Forty photographs, mainly in colour, range from the presumed site of the battle of Hastings, which prompts the observation by the author that ‘the following decades saw tension between the invading Normans and the Anglo-Saxons, even after Harold's granddaughter Edith, aka Matilda, married the Conqueror's youngest son, Henry I and the daughter she bore in 1102 symbolised the union of the old and new England' to the flotilla on the Thames celebrating the diamond jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II in 2012. The infelicitous circumstances of some royal births are recalled in the captions, not least the birth of Edward II on a building site, albeit that of the embryonic Caernarvon Castle, where it is suggested that his mother is more likely to have laboured within a temporary, timber-lined tent, rather than the still uncompleted Eagle Tower, a far cry from the twenty-first century comfort and obstetric expertise of the Lindo wing of St Mary's Hospital, Paddington, notwithstanding the more intrusive global media presence which has attended recent royal births. Finally, exploiting this particular line of enquiry to its fullest conceivable extent, some unfortunate coincidences are also recounted, for example the inauspicious arrival of the future George VI, on the anniversary of the death of his great-grandfather and namesake Prince Albert, though Queen Victoria would, no doubt, have been delighted in the continuing tradition of naming her descendants after her much-loved husband.