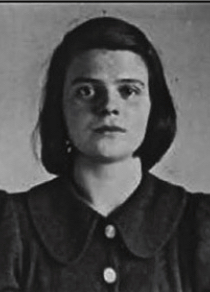

Sophie Scholl

By Lois Vincent Gobel, Elms Academy

‘Das Gesetz ändert sich, das gewissen nicht.’ The law can change but one’s conscience cannot. My local area is Munich, a place I spent a lot of my youth growing up in.

‘Das Gesetz ändert sich, das gewissen nicht.’ The law can change but one’s conscience cannot. My local area is Munich, a place I spent a lot of my youth growing up in.

In Munich especially, Sophie Scholl is a symbol of the ‘other Germany’, the hopeful Germany. The Germany that was silenced, weakened, and nearly choked off by the Nazi Government.

Sophie Scholl was a courageous anti-Nazi activist who formed Die Weiße Rose (The White Rose) during the Second World War. Die Weiße Rose was an underground organisation that distributed leaflets and pamphlets denouncing the Third Reich and their political resistance ultimately led to their arrest and execution by the Nazis in 1943.

I want us all to contextualise the time to show the true courage of Sophie. You’re a teenage girl in 1930s Germany living in Ulm. You’re being coerced into joining the female Hitler youth group, the BDM, or the League of German girls where you are conditioned into believing that your soul purpose in life is to bear able bodied children to further the Aryan race. Hitler knows that the youth of Germany are the next generation and so by preying on the vulnerability of their age he can easily ‘Nazify’ them and indoctrinate them into believing his ideology. This was the reality for twelve-year-old Sophie but even at a young age her personal conviction in defying totalitarianism remained indestructible. When a BDM leader visited Ulm to conduct an evening of ideological training, the group of BDM girls were asked if they had any preferences for discussion. Sophie suggested reading the poems of Heinrich Heine, her favourite writer. Heinrich Heine was a Jewish writer and his works had been burned and banned by the propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels in 1933. By proposing they read Heine’s works she had suggested that she still had ‘degenerate’ Jewish writings on her bookshelf which evidently showed her non-compliance to both BDM comrades and Hitler’s regime.

The social conventions for women in Nazi Germany made it even more difficult for Sophie to voice her opinion, but her passionate attitude never ceased from her youth all the way to her work in Die Weiße Rose.

Now why is this significant today? Hitler’s censorship of what is acceptable to believe and say is a hallmark of authoritarian governments across the world with some countries on the verge of the death of democracy. Her attitudes of political resistance and hope is something we need to learn from and adopt.

Instead of her works inspiring a generation that challenges political repression, her lack of international acknowledgement is causing people to trivialise her contributions instead. In November 2020, Jana, a 22-year-old anti-masker, was making a speech at an anti-lockdown protest in Hannover in which she compared herself to Sophie Scholl, believing her resistance to wearing a mask is like Sophie’s resistance to the Third Reich, one of the many examples of conspiracy theorists that compare themselves to victims of Nazism.

These attitudes play down the Holocaust for what it really was, and if we as a society in the 21st century can’t conceptualise the intensity of the Holocaust how will we make it so that it is never repeated?

Beyond that, to me Sophie is most important for what she stands for - hope. Hope isn’t something you see or touch, but it is an intrinsic part of all humans. In 1940, whilst writing about the same conflict the American writer, John Steinbeck describes hope as ‘a diagnostic human trait’ and a prime factor in our inspection of the universe. Without hope, he suggests ‘the species would have destroyed itself in despair, for ever any man were deeply sure that his future would be no better than his past, he might deeply wish to cease to live’.

This is similar to Sophie's unwillingness to reject her optimism throughout the Third Reich, even on her final days during her trial by the Gestapo, she always said something that I wish those in conflict to keep with them: ‘Die sonne sheint noch’ - The sun STILL shines.

Photograph: Gestapo photograph of Sophie Scholl taken after her capture in February 1943