Constructing and Contesting Queenship in Ninth- and Early Tenth-Century England

The ninth and early tenth centuries represent something of a ‘low point’ in the history of English queenship. Many of the women who married into the West Saxon royal family, the main English dynasty left standing after Viking conquests, are either entirely unknown or survive as little more than names. In a much-quoted passage, the Welsh monk Asser, who wrote a biography of Alfred the Great, explained that the West Saxon kings did not give their consorts the title of ‘queen’ nor allow them to sit beside the throne. In contrast to the powerful women of the late tenth and eleventh century courts, their ninth and early tenth century predecessors have remained elusive individuals. This blog, drawing on my PhD thesis on the succession practices of the West Saxon royal family, reveals the considerable influence these women could nevertheless exercise over dynastic politics.

The Evidence of Charters

Studying the presence of royal consorts in charters has allowed me to reappraise their role in this period. Charters were documents that recorded grants of land and/or bestowed their recipient with certain freedoms and privileges. The most common form was the Latin diploma, which contained a list of witnesses at the end that indicated who was present when the document was conveyed at a public assembly.

The attestations of royal consorts in this period are rare. Between 802 and 964 only seven diplomas survive that include the royal consort of the ruler. Close textual analysis of these diplomas reveals when and why royal consorts appeared publicly at assemblies, and what political purposes underpinned their attestations. These seven diplomas are marked by conscious decisions to include royal consorts when it was otherwise uncommon to do so.

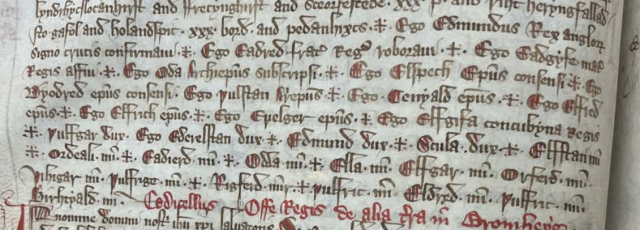

Take for instance a diploma in the British Library (S 1274) recording a grant of sixty hides at Farnham, Surrey, by Bishop Swithhun of Winchester to King Æthelbald, with an additional clause stating the land would revert to Old Minster after the king’s death. The charter was issued in 858, the year of Æthelbald’s accession, and indicates a process of alliance-building between the new king and the religious community of Winchester. After the main text, the witness-list group is constructed as four distinct columns each containing three names.

The order of the witness-list is simple enough: King Æthelbald is followed by his wife Queen Judith and Bishop Swithhun in the first column, then in turn by two ealdormen and an abbot, a second abbot and two thegns, and finally three further thegns. Judith’s presence as a queen is unique in several respects. She was a Carolingian princess who had originally married Æthelbald’s father King Æthelwulf in 855-56, prompting a a rebellion by Æthelbald presumably because he felt threatened by her status as an anointed a queen and the possibility of half-brothers with claims on the throne. When Æthelwulf died in 858, Æthelbald married his stepmother. Judith’s prominence in this document may therefore be read as a public statement affirming the legitimacy of her second marriage through the recognition of Swithhun and his community. The union contravened contemporary notions of incest and was prone to criticism from the church, including Asser, writing a few decades later. Interestingly, the diploma also invokes the memory of Æthelwulf, which may have been an attempt to project an image of familial solidarity. Judith was thus central to the political campaigning and propaganda of Æthelbald’s reign.

By contrast, a second diploma (S 340), a grant by King Æthelred I (Æthelbald’s younger brother) to a thegn named Hunsige in the year 868, provides a much fuller and differently structured witness-list: in two columns with two blocks of names. The first block consists of Æthelred, two bishops, the king’s brother Alfred, a royal relative named Oswald, and the king’s wife Queen Wulfthryth. In this case, Wulfthryth’s public presence as a queen is probably the result of tension between the king and his brother. In the same year, Alfred married his the Mercian noblewoman Ealhswith, which has been interpreted as an act of political independence. Wulfthryth’s attestation in S 340 may well have been a counter stroke by Æthelred meant to remind his younger brother of who was in charge. Æthelred’s children would be born to a queen, while Alfred’s children could not claim the same status because Ealhswith was not one.

Witness Lists: Different Interpretations and Comparisons

Because the structures of witness-lists are often missing from modern editions, returning to the original manuscripts yields important insights. For example, another diploma (S 514, Kent History and Library Centre), recorded a grant of land at West Malling in Kent from King Edmund to Bishop Burhric of Rochester, c. 942-46. Two versions of the charter survive, one from the twelfth-century Textus Roffensis and the other from the fourteenth century Liber Temporialum, with the former reproduced in modern editions and the online version. There are, however, important differences between the two witness-lists, particularly in the ordering of names.

It seems that the scribes misunderstood the witness-list of the original charter, producing divergent interpretations. Particularly important is the status of Ælfgifu of Shaftesbury, who is in a fairly low position of twelfth, away from the rest of the royal family, and given the unique status of ‘the king’s concubine’. While the term ‘concubine’ itself did not necessarily have the pejorative connotations of later centuries, a higher position would also do much to rescue her reputation if the witness-list has indeed been distorted.

Conclusions

First, a careful analysis of the structures of witness-lists, even later copies, can reveal new information about the status of royal consorts. Second, through their presence in diplomas, these otherwise obscure women could exercise public agency and power, as well as influence the symbolic messages communicated by these documents. Charters are a central body of evidence for the study of early medieval England and much ink has been, and continues to be, spilled over them; that said, my experience shows how much there is still to learn about these documents through closer scrutiny of individual diplomas and their various manuscripts.

This research was supported by an Early Career Bursary from History: The Journal of the Historical Assocation.