“Striving to facilitate the achievement of the PIRA’s aims”?

History journal blog

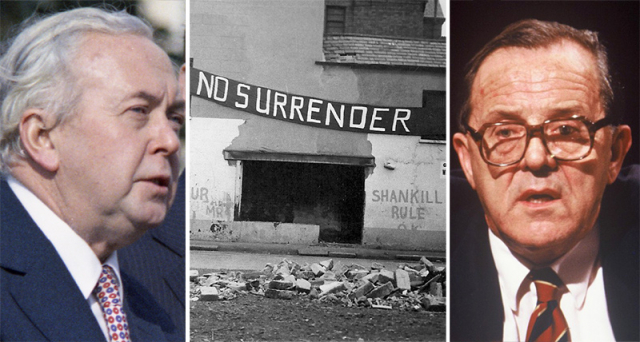

The Labour Government, the Army and the Crisis of the British State over Northern Ireland 1972–76

Professor Paul Dixon teaches at the Universities of Leicester and Queen Mary University of London and is the author of The Militarisation of British Democracy (forthcoming). This blog complements the first view publication of his History journal article: “Striving to Facilitate the Achievement of the PIRA's Aims”? The Labour Government, the Army and the Crisis of the British State over Northern Ireland 1972–76.

Huw Bennett’s Uncivil War: The British Army and The Troubles, 1966-75 (2023) claims that the Army ‘acted to save Great Britain from disaster’. By 1975 ‘military strategists’ considered the conflict ‘unresolvable’. The Army had a ‘distaste for politics’, preferring to concentrate on tactics and ‘avoid the messy political world.’ Other military historians have portrayed the Army as the ‘victim’ of the politicians and British civil-military relations as the model for emerging democratic states.

On 12 April 1975 the General Officer Commanding Northern Ireland (1973-75), General Sir Frank King, launched a remarkable public attack on the Labour government. King opposed the government’s ongoing ceasefire with the IRA (1974-75), restrictions on interrogation (torture had been used) and the release of those detained without trial. The Arnhem veteran asserted that the Army was within a couple of months from defeating the IRA, but the ceasefire had given the IRA a chance to regroup.

General King’s public outburst reflected his and the Army’s privately expressed frustration with the Labour government. On 2 May 1975 the GOC told Merlyn Rees, Labour’s Secretary of State for Northern Ireland (1974-76):

‘… that the Army’s assessment of the current security situation led to significantly different conclusions from those described by the Secretary of State. HQNI [Headquarters Northern Ireland] and all battalion commanders were becoming increasingly worried by the developments which they saw on the ground, by the current level of violence and by the Government’s overall policy, which appeared to be striving to facilitate the achievement of the PIRA’s aims.’ [1]

My article argues that there was a crisis within the British state over policy towards Northern Ireland (1972-76). The Conservative then Labour government pursued a broadly bipartisan and conciliatory policy, culminating in the failed powersharing experiment (1974).

By contrast, the New Right within the Conservative party but also powerful elements in the Army and Intelligence Services, the Royal Ulster Constabulary and Unionism opposed conciliation as ‘appeasement’ and even treachery. They claimed conciliation and rumours of British political support for withdrawal encouraged the IRA and undermined the repressive approach that was necessary to win.

From this perspective, the politicians were ‘… striving to facilitate the achievement of the PIRA’s aims’ and leading to the deaths of British soldiers, and so they resisted government policy.

The crisis intensified as more troops were killed and the Army suffered severe problems of morale, recruitment, and retention. The Army’s emergency created a need to withdraw troops and Ulsterise the conflict. But this constrained the Labour government’s ability to defend powersharing and, in any event, the Army appeared reluctant to act in support of powersharing.

Initially, Merlyn Rees dismissed King’s attack as a ‘mistake’, although he had been concerned at Army inspired leaks to the media for undermining government policy. By 1987, Rees privately told an official at the Irish Embassy in London, that there were ‘maverick’ elements in the British intelligence services (MI5 and MI6) and, referring to the allegations of Fred Holroyd, Colin Wallace and Peter Wright, he was reported as saying,

‘… There is no doubt in his [Rees’] mind that there were efforts to seriously discredit political figures both in Britain and Ireland and in effect to establish a right wing Government in Britain which would hammer terrorism be it IRA or loyalist.’

The crisis of the British state over Northern Ireland (1972-76) provides part of the context in which allegations about the undermining of Prime Minister Harold Wilson and the Labour government in the 1970s should be considered.

References

1. ‘Force levels and the ceasefire: note of a meeting held at 2.15pm on Friday, 2 May 1975’, TNA CJ4/839.