Historians in History, part 1: 1912-1939

This is the first in a new series looking at the historians who have published in History: The Journal of the Historical Association, since it was founded in 1912. The journal has a long-standing record of featuring some of the most distinguished UK and UK-based historians and its pages constitute something of a who’s who of the historical profession.

In this blog we’ll be looking at the period to 1939. In these decades the journal contained a mix of original articles, reflective review essays, and discussions about teaching history in schools and at universities.

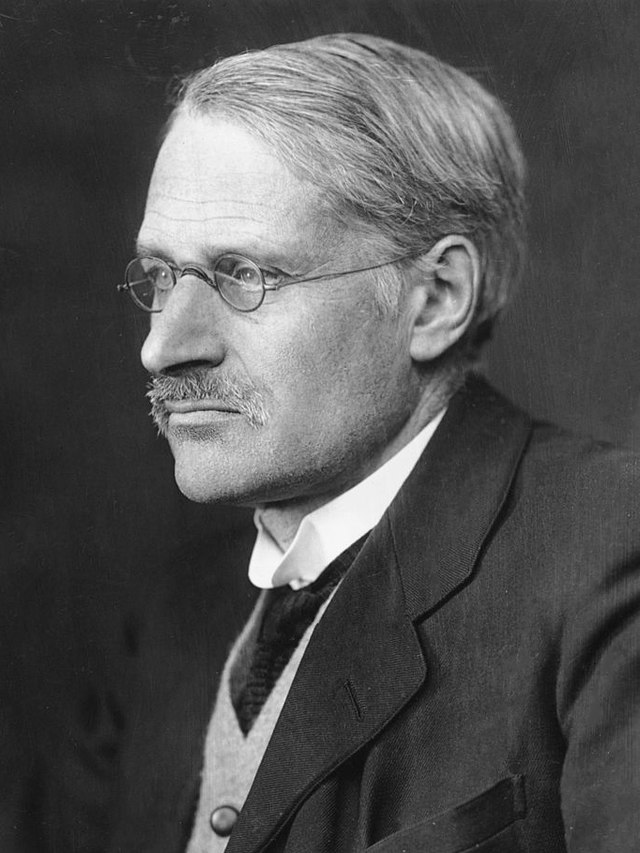

A.F. Pollard, the founding Director of the Institute for Historical Research in 1920, was a regular presence in History’s pages. His first contribution was ‘The Growth of an Imperial Parliament’ in 1916, which was based upon his Creighton Lecture of the same year. In 1926, George Macaulay Trevelyan, (pictured above) heir to a Whig-Liberal dynasty of historians, reflected upon the differences between medieval and modern civilisations in an article based on his address to the Historical Association (HA) annual meeting. This was a year before he was appointed as Regius Professor of History at Cambridge.

In its early years, the journal had a strong focus on diplomatic and contemporary history as well as earlier periods. This was spearheaded by R.W. Seton-Watson, Masaryk Professor of Central European History at King’s College London from 1922, later founder of the School of Slavonic Studies, whose many articles included ones on the history of Romania, and the importance of contemporary history, the latter based on this 1928 Creighton Lecture. He moved to Oxford in 1945, and was President of the Royal Historical Society (RHS) from 1945 to 1949.

Seton-Watson was only one of a number of past, present or future Presidents of the RHS who wrote for History during these decades. Drawing on his 1923 lecture to the HA annual meeting, T.F. Tout, Professor at Manchester (RHS President 1925–9), reflected upon the ‘The Place of the Middle Ages in the Teaching of History’. F.M. Powicke (RHS President 1933–7), a medievalist who successively held professorships at Queen’s University Belfast and Manchester before becoming Regius Professor of Modern History at Oxford in 1928, was a regular contributor. His successor as President (1937–45) was F.M. Stenton, Chair of Modern History at Reading, 1912–46 and Vice-Chancellor 1946–50. Stenton’s 1935 address to the HA annual meeting was published as ‘The Changing Face of Feudalism in the Middle Ages’.

Other eminent historians who published in History in its first few decades included Geoffrey Callender, who wrote about the naval policy of the early Tudors in 1920, a year before he took up a post as Professor of History at the Royal Naval College, Greenwich; he was appointed the first Director of the National Maritime Museum in 1937. Derived from his 1934 Creighton Lecture, Arthur Newton reflected upon ‘The West Indies in International Politics, 1550–1850’. Newton was Rhodes Professor of Imperial History at King’s College London, 1920–38. A more regular contributor was the medievalist E.F. Jacob, Professor at Manchester, 1929–44, and later Chichele Professor of Modern History at All Souls, Oxford, 1950–61. Esmond Samuel de Beer, a historian and benefactor, best-known today for his monumental edition of John Locke’s correspondence, was a frequent reviewer for the journal.

Other scholars of distinction seem to have made only one or two contributions. Herbert Loewe, of Exeter College, Oxford, 1913–31, and later Cambridge, put his expertise on Jewish history to good use in his review essay ‘Some Books on Jews and Judaism’. The historical economist, Hugh Lancelot Beales, then at Sheffield and later at LSE, wrote an article on the new poor law, which was a rare example of modern social history in the journal at this time. His book, The Industrial Revolution (1929) became a popular book among the adult education movement.

Reflecting wider gender inequalities in the profession, women were underrepresented in the pages of History. Yet there were some notable contributions from pioneering women historians. Kate Hotblack, formerly of Girton College, Cambridge, and author of a 1917 book on Lord Chatham’s colonial policy, wrote a short piece in 1922 about immigrants from the Low Countries to early modern Norwich, a topic that has recently been the subject of a special issue. Another Girton graduate, Caroline Skeel, published an article on ‘Medieval Wills’ in 1925. Skeel served on the RHS council for many years and was Professor and longstanding Head of Department at Westfield College. Drawing on a 1922 lecture at KCL, Cecilia Ady, of St Hugh’s College, Oxford, doyenne of Italian renaissance studies at this time, reflected upon its influence on English history in the 15th and 16th centuries. Hilda Johnstone, Professor at Royal Holloway from 1922, wrote about ‘everyday life in some medieval records’ in 1927, among other contributions.

Most contributors were British or British-based, but the journal also boasted some distinguished contributors from overseas, perhaps reflecting transnational scholarly networks. The eminent Italian medievalist Niccolò Rodolico, Professor at Messina and later Florence, wrote on the right of association in 14th century Florence. The French historian Élie Halévy, a regular visitor to British shores and then halfway through his monumental Histoire du peuple anglais au XIXe siècle, reflected on ‘Franco-German Relations since 1870’ that was derived from a lecture he had given at LSE. The British-born Alan F. Hattersley, Professor at the University of Natal, published on slave emancipation in Cape Colony. He is perhaps best known today for A Short History of Western Civilization, which has been reprinted many times. Two of the rare discussions of American history in the journal’s pages at this time came from leading scholars. Dixon Ryan Fox, formerly of Columbia University, and later President of Union College, essayed the theme of ‘Americanising American History’ in 1929. Thomas J. Wertenbaker, Professor at Princeton and later President of the American Historical Association (1947) reflected on the ‘Foundations of American Civilisation’ in 1936.

Most of the contributors can be regarded as historians whether they held academic posts, or were more in the vein of gentlemen scholars or public intellectuals. Interestingly, there were some contributors who were better known for their contributions to other disciplines, such as V. Gordon Childe, then the leading scholar of the pre-historic period, and Abercromby Chair of Prehistoric Archaeology at Edinburgh, before later moving to the University of London. Better known as an art historian today, T.S.R. Boase was a regular contributor to the journal. He was appointed Director of the Courtauld Institute in 1937, and after returning to Oxford rose to be Vice-Chancellor 1958-60. The Oxford don R.G. Collingwood, better known today as a philosopher and author of the posthumously published The Idea of History (1946), contributed an essay about ‘Hadrian’s Wall’ that drew on a lecture at the annual HA meeting at Newcastle in 1925, and his research on Roman history.

The journal’s interconnection with other fields beyond history was also expressed in other ways. Pollard examined ‘History and the Law’ in 1925, while Trevelyan’s classic essay ‘History and Literature’ was published in 1924. To put it another way, the journal had an interest in interdisciplinarity, although it was not called this at the time!

In the next part, we’ll be looking at Historians in History during the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s.